Relying On The Environment: Ecosystem Services

It’s easy to forget and take for granted how much we rely on the natural environment. In fact, we are one with the environment, part of a bigger ecosystem. Here we explore the concept of ecosystem services and delve into the infinite ways humans rely on the natural environment for survival and a life of quality.

What Are Ecosystem Services?

Let’s start by defining an ecosystem:

An ecosystem is complex system that is connected by the interactions between living organisms and their physical environment. Ecosystem come in various forms and sizes. A pond with insects, fish and aquatic plants can be referred to as an ecosystem. Planet Earth itself can be referred to as an ecosystem too.

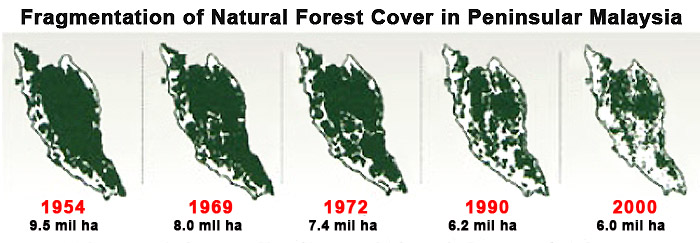

Ecosystem services are the benefits humans derive from the environment. These services are categorised into four domains: provisioning, regulating, supporting and cultural. The diagram below illustrates examples for each ecosystem service domain.

Image from WWF Living Planet Report (2016).

Do We Really Need Ecosystem Services?

Without these services, this Earth would not be very habitable for humans. Imagine living on a planet, where the soil is unable to grow crops or climate so extreme (unbearable, scorching heat or endless waves of tornadoes) that humans could not survive. Ecosystem services don’t just provide us with the basic necessities for life on Earth but allow us to enjoy this amazing quality of life through pleasing cultural, intrinsic and aesthetic values.

Rivers and forests provide key ecosystems services such as oxygen for breathing, fuel from wood, timber, drinking water, fish for consumption, hydropower, ecotourism as well as beautiful sites for camping, trekking and river rafting. Image from Pixabay (2018).

Specific ecosystems like mangroves and coral reefs protect coastlines from being eroded by strong waves and storms. Coastal ecosystems are even able to minimize damages inflicted by tsunamis! These are valuable services provided by the environment at absolutely no cost at all. If such services were not provided by the ecosystem, imagine the cost and trouble it would incur humans to build walls or coastal protection strong enough to withstand such natural forces.

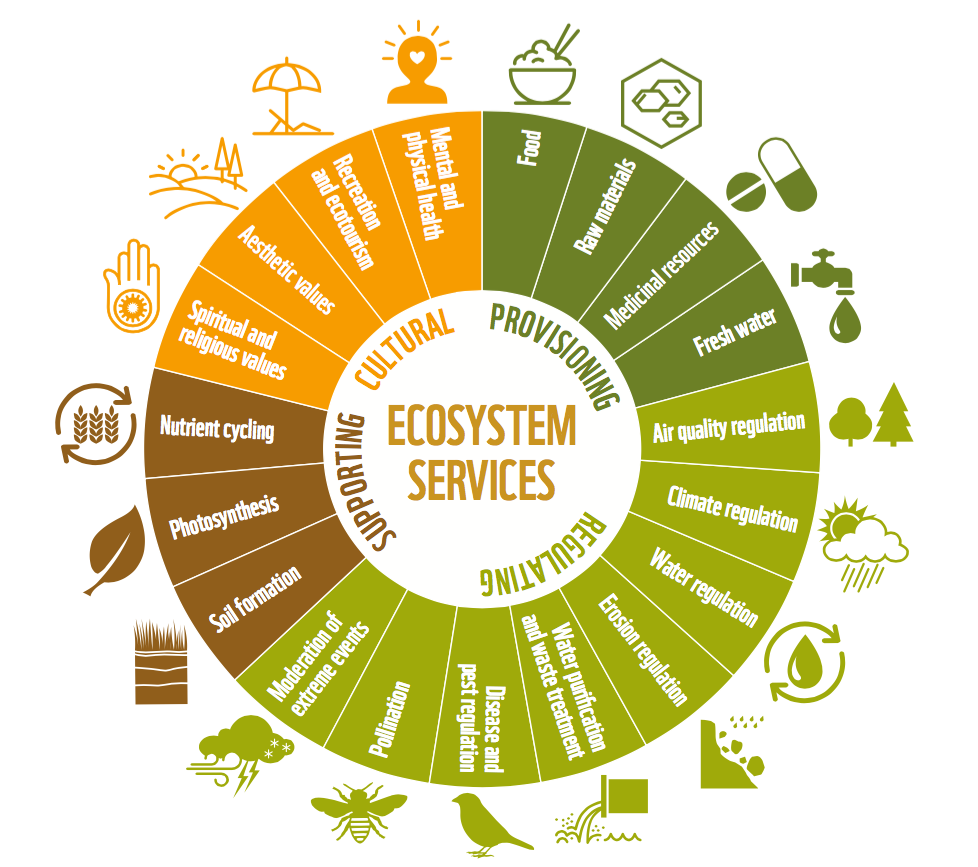

Losing Ecosystem Services

Ecosystem services are often taken for granted and are often lost through development and urbanisation. Many coastal cities around the world (China, Sri Lanka and the United States to name some) are facing such problems having lost their natural coastal protection to development. It is also costing them a fortune to replace these ecosystem services by building wave breakers and walls for storm protection.

It is important to protect and managed these ecosystem services or we would continue to lose these benefits that we rely so heavily on. In order to translate their value to stakeholders, ecosystem services are often referred to as ‘natural capital’, natural assets that provide quantifiable, monetary benefits to humans. This perspective although not ideal, allows ecosystem services to be seen as a valuable assets that need to be managed responsibly and conserved.

For more on the perspectives of ecosystem services versus natural capital and putting a price on nature, read: Natural Capital Coalition (2018).

Protecting Ecosystem Services

The key in my opinion, is striking a balance between development and conservation. This is can be achieved by incorporating natural spaces (green spaces – e.g. trees, urban forests, parks; and blue spaces – e.g. lakes, ponds, rivers) into development and planning.

One does not have to be an influential stakeholder to protect our natural environment. Voice out concerns or suggestions for the management local parks or forests. Alternatively, maintain some greenery in your garden or make some effort to keep your local river clean. This planet and the environment around us is a shared commodity. We all have a responsibility towards safe-guarding it and preserving its natural state.

Cover image from Pixabay (2018).