China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Connectivity or Fragmentation?

It comes as no surprise to anyone familiar with China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that the trillion dollar project is about more that just boosting global economy. This blog provides an overview of the BRI and the potential environmental repercussions that may follow.

The Revived Silk Road

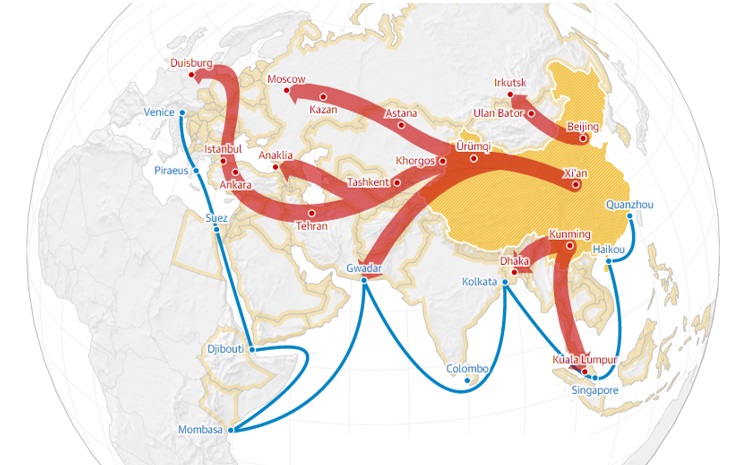

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) established in 2013 by China’s President Xi Jinping is a trillion dollar project to connect Asia to Africa and Europe through a series of land and maritime networks aimed at increasing trade, economic growth and regional integration (European Bank, 2019).

The project was inspired by concept of the ‘Silk Road’ established during the Han Dynasty, 2000 years ago, an ancient network of trade routes that connected China to the Mediterranean via Eurasia. Apart from the ’21st Century Silk Road’, the BRI has also been referred to as ‘One Belt One Road’.

The Belt and Road Initiative spans across 71 countries, including 60% of the world’s population and over 1/3 of global trade (The World Bank, 2019). The image visualises the belt land corridors (red) and maritime pathways (blue) connecting China (yellow) to parts of Africa, Asia and Europe. Image from The Guardian (2018).

The project ultimately enables poor, underdeveloped countries to obtain hard infrastructure (through Chinese investments) that would boost local economies which otherwise would be nearly impossible to achieve. Hence, the key nations targeted in the BRI are countries like Myanmar and Pakistan that globally rank 145th and 147th respectively in the United Nations Human Development Index (HDI) (ChinaPower, 2019).

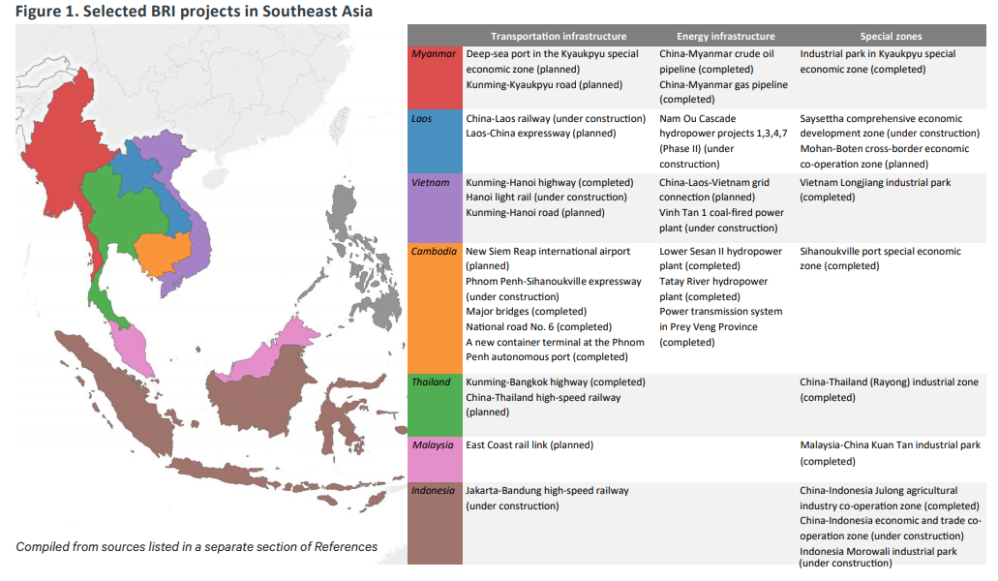

The BRI doesn’t just intend to build infrastructure to connect nations in terms of transportation. Railways and maritime routes aside, the project seeks to establish energy infrastructure and “special zones” within participating nations that would generate economic revenue for both the nation involved and China. We’re talking hydropower dams, deep sea ports, crude oil pipelines, coal-fired power plant, gas pipeline, grid connections, major bridges, highways and numerous industrial parks (these are just a select few from Southeast Asia)!

List of special zones, transportation and energy infrastructures in various stages of planning and construction within Southeast Asia as part of the BRI (Stockholm Environment Institute, 2019).

At present, the plan extends to 65 countries with a combined GDP of $23 trillion and includes about 4.4 billion people. For more overview on the BRI, watch this video!

Ecological Fallout

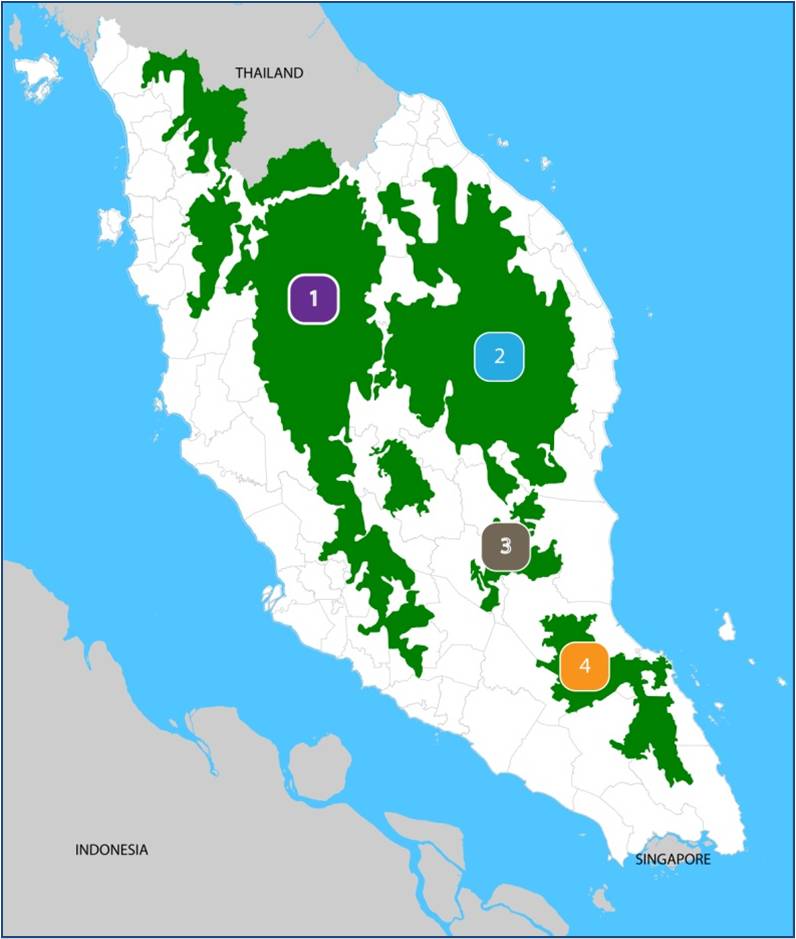

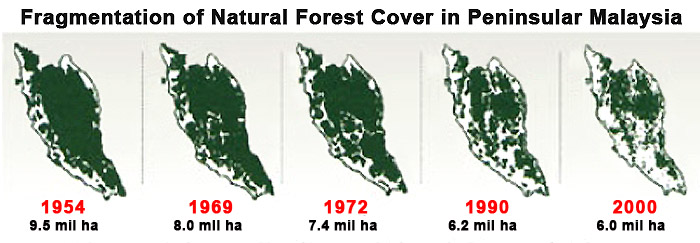

The six continental corridors providing key linkages in this project involve highways, rail lines and dry ports located within remote and highly biodiverse areas. Likewise deep-sea ports and cargo centers dotted along the coasts of the South China Sea and Indian Ocean are known to encroach ecologically sensitive areas (EESI, 2019). Over 1739 Important Bird Areas and Key Biodiversity Areas are at risk of disturbance, with further potential for detrimental impact to over 265 already threatened species.

Several projects have received fierce protests and condemnation for the threat it poses to native wildlife and their habitats. The building of a BRI dam in Indonesia would mean flooding and destroying a huge portion of the Batang Toru jungle, which is the only known home of the world’s rarest great ape, the Tapanuli orangutan. Although multilateral financiers have deemed this project too ecologically detrimental to fund, the state-owned Chinese company running the project may well receive funding from the state-owned Bank of China.

A Tapanuli orangutan — the species was only discovered in 2017 and is already facing extinction with only over 800 individuals persisting in the wild. Sign a petition to stop their habitat from being destroyed. Image from Rainforest Rescue (2019).

These types of project also threaten the livelihood of people who rely heavily on local environmental resources especially due to alterations to ecosystems. A proposed dam in the Mekong River, Cambodia, could severely reduce local fishery yields, affecting not just fishermen in Cambodia but downstream in Laos and Thailand too. Moreover, the increased access to undeveloped areas of forest through transportation infrastructure increases the likelihood of poaching and deforestation in those areas — a dilemma that has been plaguing, particularly poor and biodiverse, regions like Southeast Asia.

And we have not even explored the energy paradox China presents — promoting coal fired power plants and infrastructure to export fossil fuel through BRI, despite China’s growing domestic interest in renewable energy. The repercussions of a developing nation relying heavily on non-renewable energy such as coal, which is being phased out globally, is a whole other concern.

The environmental controversy of the BRI is real. Know what’s happening near you and do your part to ensure the homes of thousands of other living beings are not destroyed in our human effort to better our’s.

Further reading is available through the links below.

Cover image from Pixabay (2019).